Ishaan Mehta

$ cat ~/projects/os

Forewarning I am not experienced at any of this, and this entire project is my attempt at making something. The explanations are my understanding of whats going on and may be riddled with errors.

Operating systems are real neat. They turn your fancy number machine into a world of buttons and text, and it's all done through mysterious magic written in the dark ages before civilization. Or so it seems at least. I think making an OS would be neat, not because I would want to be able to daily-drive my own custom system or anything, but because they seem like a good way to learn what an OS actually does. Plus if they really are written using magic, then I get to be a wizard so thats cool.

Part 1: 16 bit to 64 bit, a dramatic retelling

Making something that boots is really easy, like suspiciously so. Its not a lot of code, just a quick assembly file and some special numbers cause computer scientists can't enough of their special numbers

Thats it! Like no joke if you compile that using nasm and output to a binary file, you will get something that will boot on x86_64 devices. Its not much, it starts and immediately hangs until the heat death of the universe, or CPU whatever happens first, but it boots.

But Ishaan, you ask, what the hell does any of that mean? Well dear reader its really simple (smile now cause it won't be anywhere near simple later). The first line just tells the computer that we're using the 16 bit mode instead of the full 64 bits. We do this because when the CPU starts up, it likes to do that in 16 bit 'real mode'. Why that happens is beyond me, but it is what it is and we must adapt to the choices made by the ancient ones of the early 2000s. Anyways after that the second line make _start a global label, so it can be accessed from anywhere, we didn't have to use _start but its like standard convention and who am I to mess with that. Then we create our infinite loop, which if you can read english should make sense (not meant as a dig to those who can't), since it defines _start as a label on line 4, then jumps (it doesn't say jump but its like 1 letter removed and thats close enough) back to the label _start we defined on line 4. After that it pads out the file with 0s so its exactly 510 bits long, then it slaps 0x55AA into the 511th and 512th bit creating our perfect 512 bit bootable file. What is 0x55AA and why is it reversed in the code you ask? Well the latter question is easyish, it just has to do with endianess.

And so it begins, the first stupid choice made by a bunch of nerds in the 90s about how computers should do things. When computer people refer to endianness, they just mean the order in which data is shoved onto your storage device. Big Endian is the form we usually think in, it puts the littlest end of the number in first, then the second littlest, then the third, etc etc until you've put your whole number in. It looks something like this:

So nice and so neat, but some of the nerds decided that was lame (they had decent reasons, go google them its actually rather cool) and ended up using Little Endian. That's where the opposite happens, the biggest end of a number is shoved in first, then the second biggest, etc etc you get the vibes. That looks something like this:

Nice and confusing right? Anyways the reason this matters is because the x86 architecture is Little Endian, which means data is shoved in backwards to the way you would write it. All that to say that's why we put 0xAA55 on line 8 instead of 0x55AA, because the cimputer thinks of the data in a weird way and we must work with it. As to why we specifically wanted to put 0x55AA into the 511th and 512th bit? Thats just a magic number. Its not random because it was chosen due to its alternating form in binary (101010...) making it very easy to see and less likely to be generated by whatever garbage data is in storage so the computer doesn't get confused.

For funsies I wanted to slide a little 'Hello, World!' message in right after booting, so I set up a quick print16 utility:

Basically all this does is dump a bunch of bytes into the console output until we hit a 0 (also known as a null-terminator) after which we return to where we were. The actual function is pretty simple: it steps through the string stored in si, checks if the value is 0 and if it is finishes the printing, otherwise it just drops the ascii encoded character into the console output and loops to check the next character. The character gets stored into the al register, but the real neat thing is setting the ah register to 0x0E. This makes the ah represent the teletype function, which if you can't tell types stuff. Line 9 runs the function in the ah registers (which we know is teletype) from interrupt 0x10. Combining all this gets us a nice 'Hello, World!' out to the console.

Back to the serious stuff, we need to move on from 16 bit mode because this isn't the old days and 64 bit computing is where all the fun is. There's a few different roads we could take to get to the goal of 64 bits, but I chose to take the more scenic one that drives us through 32 bit stuff. So away we go making the jump to 32 bit power and entering whats known as protected mode, called that because it allows for virtual memory addresses and lets us enforce some nice memory and IO protection measures to keep the OS nice and safe.

To get to 32 bit stuff, we need to go set up a Global Descriptor Table (or GDT). A GDT manages how memory is accessed and how its protected, it lets you mark areas as executable or writable and all that neat stuff. It's split into two important bits, the code segment and the data segment. I'll be completely honest, no clue how most of this stuff works well enough to explain it or write about it in any capacity, but there are links at the bottom of the page to learn more and see where I got help/guidance from.

After setting up the GDT with a kernel level code and data segment, I had successfully entered 32 bit protected mode. To make the final jump to 64 bit long mode, there was one main thing I needed to do (Technically 64 bit mode needs another GDT but I don't want to sound repetitive), setting up paging. Paging, you ask, whatever could that mean? Is it mayhaps, when you use 'pages' of memory to protect certain segments and allow other segments to be modified by the user? And thats exactly it. There's a couple different types of paging we need to setup: PAE (Physical Address Extension) which allows for virtualized memory addresses, PML4 (Page Map Level 4) which lets us address a larger amount of RAM, and the whole PML4 -> PDP -> PD chain.

Quick Side Note: Virtual memory addresses are just us lying to the computer. To oversimplify a bit, lets say that address 0x12345 is the starting address for a process, but we don't want to have to make the process try to figure out where things are relative to whatever address it starts at because that starting address changes a lot, so we tell the process that 0x12345 is actually 0x00000 allowing the process to just have to know the locations of everything relative to 0x00000.

Anyways setting up paging is pretty simple, just define where each page is located in the assembly file like so:

After that you need to load all the initial data into the pages so we can use them properly, which means establishing entry points for PML4 pointing to the PDP, then for the PDP entry points to point to the PD. Then just fill the PD with its identity map (that just marks it as present and writeable, then sets up the page size. And once you finish that we can make another jump off to the final land of 64 bit long mode.

After that harrowing journey we finally arrive at Mount Doom, ready to take on the world of whatever comes after creating a bootloader. I threw together some basic code that sets up a VGA mode and clears the screen and we're bascially set:

Et voila, we've gone from 16 bit real mode all the way to 64 bit long mode, with a detour through the 32 bit land. Now what you may ask me? Well we must load a kernel and start getting our operating system setup. But how do we do that you ask? Well I may know now, but I didn't when I was writing this code, and so we must say goodbye to all our work on this very nice bootloader and switch to something made by people who know what they're doing. My choice for this was Limine, mostly cause it seemed pretty cool and since this is just a toy project it isn't super important which bootloader I pick

Part 2: Loading a kernel and getting everything setup once again, a less dramatic retelling

Now that we're using a properly made bootloader, we no longer have to rely on the VGA tech from the dark ages. But first things first we have to setup some basic kernel stuff to get ourselves off the ground and begin our long flight to Operating-Systemhood.

What? Assembly is evolving! (doodly toot toot or whatever the noise is). Congratulations! Your Assembly has evolved into C!

Thats right folks! We now finally can use C to code our operating system, which gives us a whole host of new functions. Or so I thought. You see usually when I code in C, I'm coding on an operating system (wow shocking I know), and those operating systems have something known as a C Standard Library (wow also shocking, shut up this is relevant). But since we're coding an operating system, we have no standard library, nor anything of substance. So we instead have to rely on base C, meaning life just got a whole lot more compilcated. For now however, thats not our concern.

To get started I included the limine.h file from link 12, and then started getting my kernel made. Since we aren't using the VGA Text Mode anymore we instead have to use a framebuffer, which is just a large array of RGB values that represent what's currently on the screen. Luckily we don't have to make this from scratch, since we're using an actually good bootloader and Limine provides one to us, so we can get access to it like so:

And if all goes well, we should be able to check the response to this request later on and get access to our lovely framebuffer. We do need set some things up before we get there though, since we're compiling our C code before writing it to our operating system and our compiler (gcc, but clang should expect this as well) expects that we declare a couple of memory functions as well as one function that will be incredibly useful through development:

Now that we have the boilerplate stuff finished, we can get to the fun stuff. We need an entry point for the kernel, somewhere that the bootloader can hand off execution and where the kernel can initialize everything and start doing its kernely job. In that entry point function, we can start doing checks of whether or not everything has loaded and then start drawing stuff to the screen. First things first, we have to make sure that our bootloader is the correct version and will actually do what we expect of it, which is just an if statement that calls our fun halt and catch fire (hcf) function if it fails. Then we validate the framebuffers existence by checking whether or not our request for it succeeded, then checking if the request actually found any framebuffers for us to play with. And after all that, we can write our bytes to the framebuffer and get the screen to display something cool. But how do we do that, y'all ask. Well its really quite simple, you just get the (x,y) coordinate of where you want to draw something, then you slap one of those hex color codes into it:

A couple things to note: the x and y values are of type size_t and not int because they're expected never to go negative since that would take us out of bounds of the framebuffer, the fb_ptr is volatile since other things may mess with the framebuffer later and we need to tell the compiler that thats okay, and the y is multipled by a modified framebuffer->pitch as that lets us index the rows of the framebuffer properly and treat each y increment as a full row being skipped. But after all of that, we've drawn a diagonal line down across the screen (or at least across the first 100 pixels of the screen).

And now we're done right? We can draw things to the screen, and thats all an OS really needs to do. Unless, y'know, you want to get keyboard input, or run more than one program at a time(this counts the kernel as a program), or make sure the user doesn't have the power of a god over the entire computer. So away we go again, setting things up for the 3rd time now but getting real close to almost being at the starting line of making the OS work correctly.

Part 3: Yay Graphics!!

So the kernel is loading and we can draw to the screen, normally that means we totally forget about the screen until we finish making a bunch of other stuff like memory managers and interrupt handlers (authors note, foreshadowing is a literary technique in which a storyteller gives an advance hint of what is to come later in the story), but thats less fun than making text render so we're doing that first.

But to get text to be all texty and lettery, we need a font. Just use a TTF or something you say, but how can we use a TTF file when there is no filesystem yet? Why isn't there a filesystem yet, you ask with wonder in your eyes, well because thats a much later thing and also because filesystems rely on a bunch of stuff we haven't even thought about yet. So then a bitmap font, not resizable but we can encode it into an array and just use that for everything ever. How does one encode a bitmap font you ask, well its rather simple, you just convert every character you want to be able to display into a grid of black and white pixels. If you're smart and think ahead you'll use some multiple of 8 as the size of the grid, because then every single row can fit nicely into an integer variable and we can just store a series of numbers rather than the whole grid of 1s and 0s. I chose an 8x8 font, mostly cause its smaller and easier to make, and set it up like so:

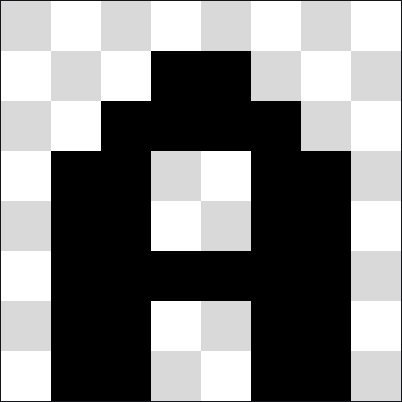

Now that just looks like magic numbers, but if you unwrap each one you get this:

If we just do that for the rest of the letters of the alphabet, plus a couple more symbols like ! so I can truly show my excitement, a font is born! Next comes actually drawing the font to the screen, since we dont have any rendering libraries (or a standard c library) we'll have to DIY some kind of system. The easiest solution is just take in a string, go through it character by character, and then just copy the 8x8 set of pixels corresponding to the character. So away we go implementing that:

You may be wondering why I didn't take in a length for the string, or why the while loop just loops while the string ... is? Well C uses this lovely thing called null-terminated strings, which means at the end of every string constant you create there exists a single extra byte thats set to 0. By using this extra byte, C is able to know the length of strings by just looping until you hit the 0, which is how our while loop works. It checks the current value of the string pointer: if its 0 then it'll stop, else it'll go through and print out the character to the screen by drawing it pixel by pixel (I'll explain that in a moment). The reason I don't have some kind of for loop is because of another quirk when using strings in C, since a string isn't really a thing. Theres no datatype string thats built into the C language, instead we just use an array of chars. Because of this when passing a string literal to a function, you take in a pointer to a character (the code assumes it's a valid string and not some random memory address). The increment operation done on line 21 shifts the pointer over 1, for example:

Eventually str gets shifted to the null byte at the end of the string and it'll stop the while loop, allowing us to not have to use any extra variables to keep track of where we are in the string.

The pixel drawing looks a big complicated, buts it's rather simple once you understand it. We establish one loop that goes through the 'rows' of the image (each 'row' being an element in the font array), then create another that goes through the 'columns' of the image (each 'column' being a single bit in the byte). The >> operator just shifts a number to the right a certain amount of bits like so, and by performing a bitwise AND on the number with 1, we can check if the bottom bit is set: if so we can draw a pixel there, else fill the area with our background color.

Notice how that final 1 got shifted out of the number, and a fresh 0 got shifted into the top. By doing this shifting we can check each bit of the byte, and use that to determine whether or not to draw a pixel. While this method does let us save on storage space, the font gets reduced to 2 colors, forcing us to add some kind of extra code if we want to change the colors of the text. But thats a future problem, for now we're able to get text from our code onto the screen, isn't that exciting!

Part 4: Memory Allocation

We have a screen, we have a kernel that loads and lets us write text to the screen, and now we must wrestle a dragon and tackle memory management. It sounds easy on paper, we have all of RAM at our disposal, just take a chunk and get to work right? If only it was that easy; since we're loading all sorts of data into the kernel, such as the GDT or eventually interrupt data, that has to go somewhere and it could be anywhere in RAM for all we know. Luckily we do not have to try and figure out what areas of memory are safe for us to mangle, as our favourite bootloader Limine handles that for us. Earlier we had made a request to capture the framebuffer, and now we must make another to get access to the memory map that Limine provides us with:

The process is about the same as getting the framebuffer, we create a request that has the memory map request id and then when initialising memory we check if the request was succesful. If it was, we can now just loop through every entry in the memory map, and check if its been marked by Limine as usable, or if its being utilized by something that we don't want to mess with. To make the process easier, I just stored a pointer to every usable section of memory in an array, so I don't have to loop through the entries every single time. But now comes the big decision, how do we differentiate between usable (also reffered to as 'free') data, and data thats in use. I can't just assume as sections of data that's full of zeroes is free since sometimes a we might want to set data to zeroes and then later change it. Some people use magic numbers or just 'free' and 'used' labels, but I decided on a header system. Whenever the kernel tries to allocate a block of memory, it starts at the beginning of the first usable entry in the memory map. It then checks the header, split up into 9 bytes. The first byte tells us 3 things, whether or not the header represents free or used data, if the data the header represents is all in one line or split up across multiple data segments, and how long the actual header is. But you just told us the header was 9 bytes, you cry, and I may have bent the truth a little. But for now lets assume the header is 9 bytes, and that data is always in one segment, not split up. The next 8 bytes (8 bytes is 64 bits, and we're using a 64 bit system ... I wonder if those two have any correlation) represent the memory address for the byte after the end of the data. All in all it looks something like this:

Thats the header for 'Hello World', which is 11 bytes long, plus that null byte we put at the end of strings to mark where the string ends, which makes 12 bytes total. Since we start at index 0 and not index 1, the header points to index 12 as the point after all of the data contained by this header. But we can't just give the kernel the header, cause then we'll have to manually skip ahead through the header every time and that'll get really annoying, so whenever the kernel tries to allocate memory we'll return the address of the start of the data (for the 'Hello World' example this would be the address where the 'H' is stored). The code for this is weirdly long and complicated, but that might've just been me. I'm not going to explain it all for sake of time but its vaguely commented:

The only thing I will note is that NULL (which is the same as a pointer to 0x0) gets returned if no memory could be allocated, since that makes error handling easier as no one has to deal with strange corrupted memory, and no one has to try to figure out if the memory they got is actually valid and usable.

Part 5: Onwards and Upwa- wait why are you packing up

This is a super neat project, baby's first operating system taught me all sorts of things about how my computer works under the hood. The journey was shortlived, and really quite interesting, but moving forward is more effort than I believe it to be worth to me at the moment. While getting a fully functioning operating system, with a user mode and program management and all that, would be cool, the road from here gets more and more complicated. I don't have the knowledge and programming skills to understand it all just yet, but when I'll return when I do and BSOS (baby's second operating system) will be a thing to be reckoned with. Or at least, a thing to be vaguely poked until it starts crying like an actual baby.